On the night that Jumai was kidnapped from the Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok, she called her dad.

She was in the back of a truck, packed in with her schoolmates as men with guns tried to take them away. Her father, Daniel, told her to jump out of the van - but then the line cracked and the signal dropped.

He ran out of the house to try to find phone signal. When he called back, a man answered: "Stop calling, your daughter has been taken away". Daniel realised then that her fate was "in the hands of God". The next day he tried to call again but the line was dead.

Although some families of the missing girls were happy for us to use their photos and names, we have changed the names of Jumai and her father to protect their identity.

Until the girls were taken, the area around Chibok had been relatively peaceful. Islamist militant group Boko Haram had attacked villages further north and east but this busy market town had escaped.

Daniel, who lives in the nearby town of Mbalala, sent his daughter off to school on 14 April 2014 to sit the first of her final exams.

But late that night, in one of the most organised attacks of its insurgency, Boko Haram stormed the school compound and kidnapped Jumai, along with 275 of her classmates.

His daughter never managed to jump off the truck, like some girls who managed to escape. But Daniel has not yet given up hope that he will get her back. The two were very close.

"I understood her the best," he says. "She worked harder than any of her three brothers and she rode a motorcycle like a man."

A few months ago, Daniel decided to try his daughter's phone number again. A man's voice answered:

"This phone belongs to my wife, what do you want?"

"Who are you?" Daniel replied.

The man said: "Who are you?" Daniel ended the call.

A few days later he called the number again. Again the man answered.

"Why are you calling this number?" he asked.

Daniel lied: "I am calling you because I knew you from Maiduguri" - the largest city in Borno state.

"If you did know me you would not dial this number," the man replied.

He called himself Amir Abdullahi - addressing himself as a militant leader. After that, Daniel didn't call again.

Empty town

Jumai is from Mbalala, a town about 11km south of Chibok and one of the worst-hit by the kidnapping. Twenty-five girls went missing from Mbalala alone.

Once a busy market town, where traders went from as far as Kano to buy beans and livestock, now the stalls are empty. The wooden bones of market stalls still fill the main square.

These days the army restricts everything people do here - they can't buy food in bulk or even cooking gas, generators can't run at night, so people just go home to darkness.

With no schools and no work to do, young people no longer stay here if they have the choice. Boys leave to find work elsewhere, girls of age get married as soon as they can.

Plying the little trade they can, women sell homemade snacks from plastic tubs at the side of the road.

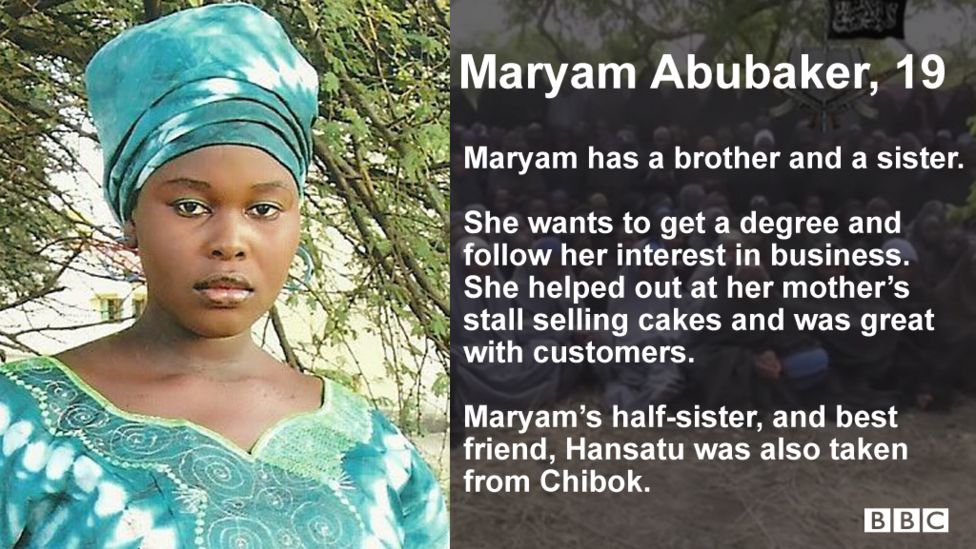

When she wasn't at school, Maryam Abubaker used to help her mum sell these snacks, bean cakes and noodles. On the day that Maryam was kidnapped, just before she headed off to school, she was helping her mum at the stall.

"She made $50," her mum told us. "She is a great businesswoman. She was very lazy on the farm, but she was great with customers."

That was the last moment that Binti had with her daughter.

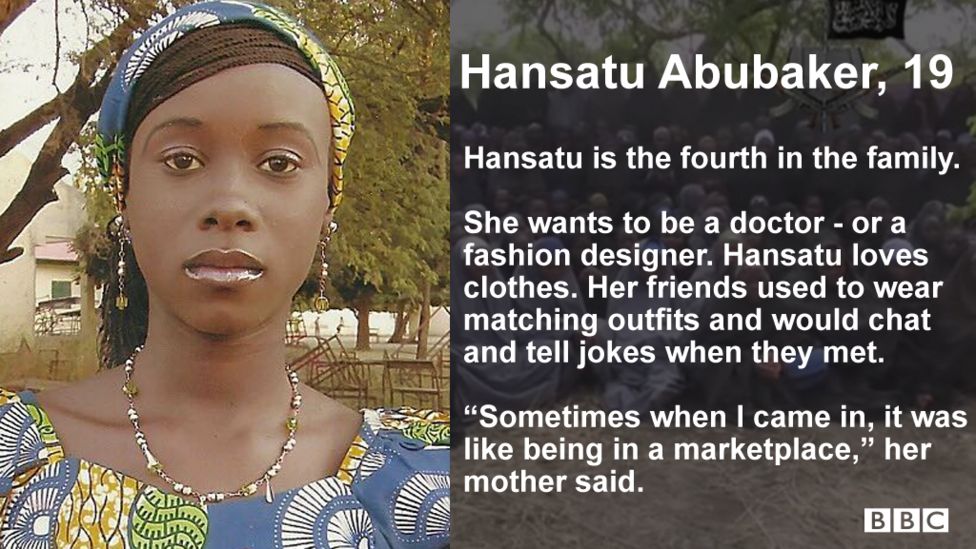

Maryam's best friend was her half-sister Hansatu. They did everything together, they shared the same friends and even made matching outfits for each other.

Hansatu loved fashion and wanted to be a designer. Just before she was kidnapped, she begged her mum to buy her a sewing machine.

After she disappeared, her younger brothers and sisters would see the clothes she left behind, they would ask where she had gone and when she was coming back. Eventually her mother bundled the clothes into a bag to stop the questions.

She shows us the outfit that Hansatu was supposed to wear on her friend's wedding day, a few days after the exam, which never happened.

"I am going to keep it until they come back," she says.

These belongings are the little that these parents have left to hold on to. Since their daughters were taken, they've received no information from the government on where they might be.

The last president refused to engage with the parents but even the new administration has done little to try to track them down. The truth is, no-one has any real idea where they might be.

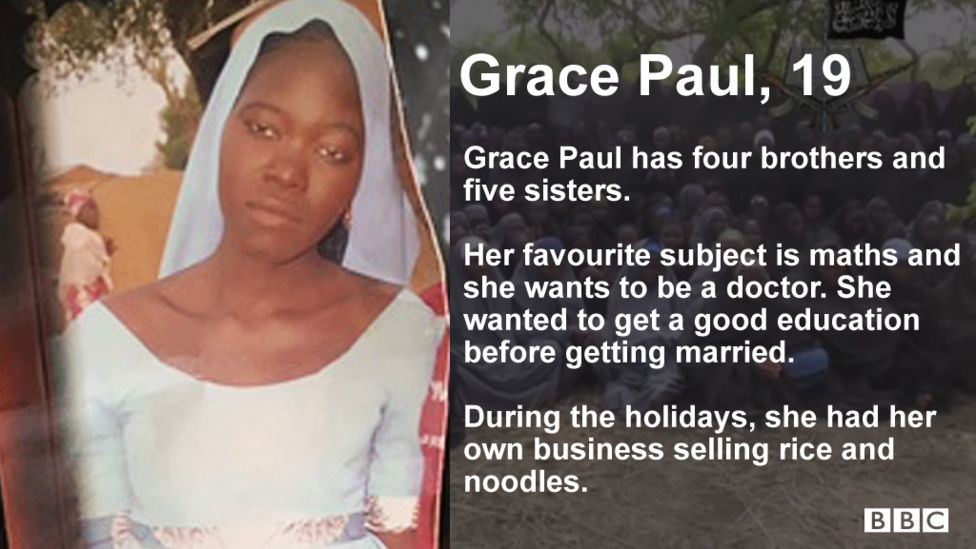

For the family of Grace Paul, one photo is all they have to hold on to. Grace would be 19 now. She was a lovely singer, according to her dad. She loved maths and wanted to be a doctor.

The family have entrusted their last photo of her to their neighbour Aboku Samson to make copies of it for them.

The girls at Chibok secondary school represented the most ambitious young people in their village.

In a country where less than half of young people finish secondary school, they were the few in their community pushing for an education. And some had to fight for it.

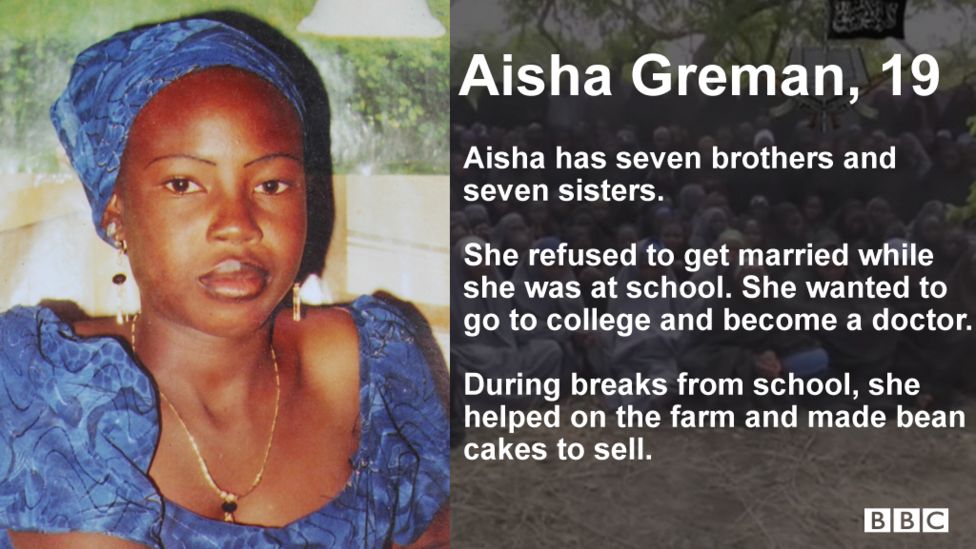

Aisha Greman was 17 when she was kidnapped. Her father says she refused to get married while she was at school, though she was asked.

She was a hard worker and wanted to get to university so she could be a health professional.

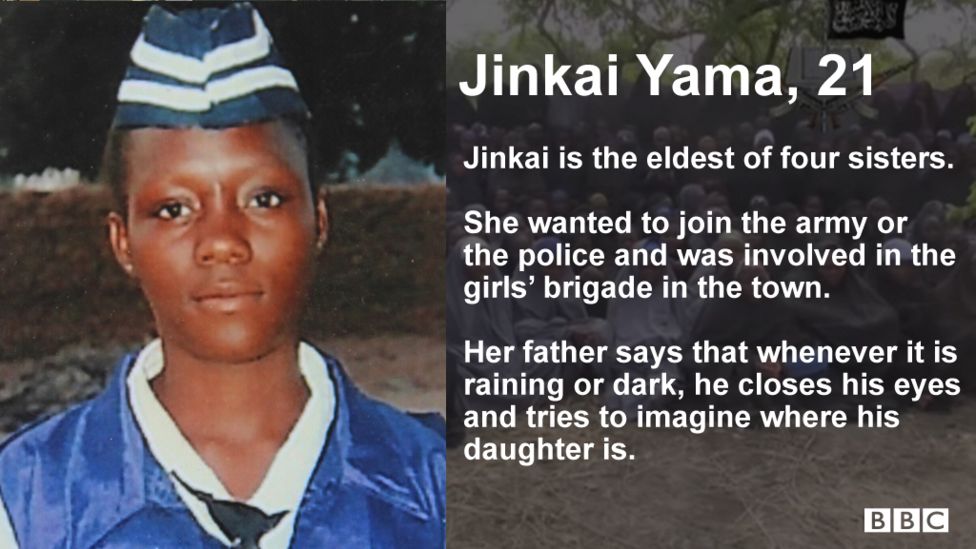

Jinkai Yama was the oldest in a family of four girls. She desperately wanted to join the army and was a proud member of the cadettes girl's brigade.

Her three younger sisters ask about her all the time. Last month, when there were reports that a girl from Chibok had been caught alive in Cameroon, they were convinced it was her. But the girl turned out to be from Bama, a town much further north.

Whenever it is dark and raining outside, Jinkai's father closes his eyes and tries to imagine where his daughter is. Like many of the parents here, he has almost given up hope.

He and his wife don't believe the government is doing anything to find them. If they did, her mother says, they would have sent a team to Cameroon straight away. Instead, it took three days.

The mistrust is so deep that conspiracy theories abound.

Jumai's father Daniel believes his daughter's phone number is key to his daughter's whereabouts but thinks the government can offer him no help at all. He refuses to hand over the number to them.

Attack warning

The army seldom come to Mbalala, but every Sunday they pass through to shoo small traders away from the marketplace. The region is under lockdown after a series of suicide attacks. They are afraid of any place that people might gather.

When we visited, the army told us to watch out, that anyone could be a suicide bomber. By that, they even meant girls. Over the past two years, many of the suicide bombers used by Boko Haram have been girls.

They've attacked refugee camps and market places all over the region. In February, they attacked the market in Chibok town, just down the road, killing 13 people.

This fact hasn't escaped the parents here, though it can't be easy for them to accept. One mother told us how she felt about these accusations - that her daughter could be a killer. She refuses to believe it.

"I gave birth to that baby," she said. "Even if she comes to me with a gun in her hand, let her kill me, but I will still welcome her."

No comments:

Post a Comment