It was an old, fuzzy photo of an amateur football team - lads like ones you might find anywhere in the world. But three decades later, their small town in north-west Syria was engulfed by war. What became of those 13 young men?

When I first saw the picture, I was immediately fascinated. It was a big, blown-up photo of a team in shiny green-and-white kit, with the kind of luxuriant hairdos and moustaches that remind you instantly of the 1980s - a picture, I thought, of youthful innocence. Nearly 30 years had passed since it was taken, and we were in the middle of a war. So I wanted to know what had happened to those lads.

The picture was on the wall of a sports complex in Syria, on the edge of the small town of Marea, just north of Aleppo. It was late 2012, more than a year into the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad, and I was there to report on the intensifying civil war. Government jets were bombing rebel-held Marea, so I stayed at the sports complex with its surreally expensive-looking artificial grass pitches, because my host, local journalist Yasser al-Haji, said it would be less of a target than the centre of town.

Yasser, it turned out, was in the photo himself - standing on the far right of the back row. He had been the founder, coach and captain of the team. In the mid 80s, when the picture was taken, he told me proudly, they were giant killers. They beat big professional teams from the city of Aleppo to win the provincial championship - even though they were small-town amateurs.

"It's painful to look at that picture," he says. "I've very emotional, conflicting feelings about what we did and what happened to us."

Three years ago, Yasser told me only that they'd been divided by the war. But now, with his help, and a lot of international phone calls, I've pieced together their story. It's the story of a group of schoolboys from a poor, dusty town of farmers and traders who started off kicking a ball around on a bit of wasteland.

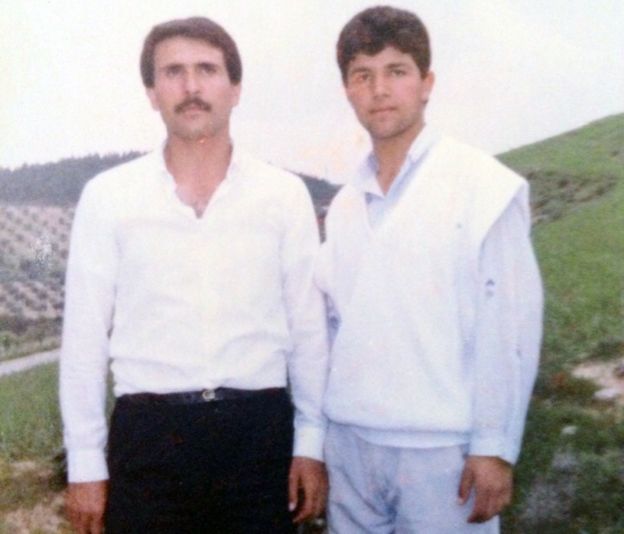

There was Bassam, the goalie, serious and hard-working (back row, second from left). He dreamed of becoming a professional player. There was Muhammad al-Najjar, nicknamed Perfume Man (back, second from right). They say he was as interested in fancy clothes as fancy footwork.

Then there was Raed, the baby of the team, small and thin but desperately keen (front, third from right)... Abdul-Rahim, wild and impetuous, with a particularly unruly mop of hair (back, middle)… and Muhammad al-Farouh, the tall, neat, athletic striker who led the singing in the bus to away matches (back, third from left).

Plastic boots were all they could afford. "After the game our feet smelt so bad," says Yasser. Football culture was rough in provincial Syria - sometimes their opponents' fans pelted them with pebbles, sometimes with sheep droppings. But Yasser persevered. He was a charismatic teenager and he built a winning team.

But behind it - and you can sense this too in the photo - there was also sadness.

"The situation was certainly tense - that's why the only breathing space for young people was sport," Raed al-Najjar remembers. The picture was taken soon after the Hama Massacre of 1982. That's when the regime of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar's father, is believed to have killed at least 10,000 people, possibly twice that number, following an Islamist uprising.

There were other executions and disappearances all over the country too. Raed's father, a politician who supported the wrong side when the ruling Baath party split, was taken away by the secret police and never seen again. Raed was then just 10 years old.

"I was always afraid, afraid of everything, because our regime is very harsh," he says. "To this day I don't know where my father is, whether he's alive or not… It's better not to try to imagine, because it's so awful what happens in our prisons - it's better to think he died a long, long time ago."

Yasser al-Haji

Yasser al-Haji

With a father in jail, Raed knew he'd never get a good job. So when he was 24 he went to study in Russia where he became a successful businessman owning two restaurants.

Yasser, the charismatic coach, also left Syria in the 1990s for political reasons. He had been a sports teacher then a journalist, but his articles became too critical of the authorities and he was warned he'd be arrested unless he fled abroad. First he went to Germany, then the US.

He came back to Marea to join the first protests against the Syrian government in early 2011. A few months later, Raed followed. Government troops had abandoned the town, and together Yasser and Raed achieved their dream of building a proper sports ground and children's playground in Marea - the sports ground where I later stayed, and first saw the team photo.

Raed al-Najjar

Raed al-Najjar

The day it opened, they reunited all the old members of the team to play together again. "It was the happiest day of my life," Raed remembers. "It was like we were born again. But it didn't last, because evil came, the evil of war… We were all blown in different directions, and now it's empty, that pitch. I don't think when I remember that. I just cry."

The regime was bombing Marea relentlessly, and the walls of the soccer complex were soon pitted with shrapnel. Raed returned to Russia, and Muhammad al-Farouh, the tall striker everyone had admired for his running and singing abilities, decided it was too dangerous for his family to stay in their home town. One snowy dawn in early 2012, he drove them on the perilous route over the border to Turkey, to the safety of a refugee camp.

Another old teammate, Hussein al-Khateeb, also fled with his family to a Turkish camp after regime troops returned briefly to Marea and set light to many homes, including his, with phosphorus grenades. But others have stayed - even though militants of so-called Islamic State (IS) are now besieging Marea on three sides. They are just 1km from Raed and Yasser's beloved sports ground - the pitches, and the team photo are in the crossfire between IS and other rebels.

Abdul-Rahim, the impetuous one with the wild hair, is now a fighter with the Free Syrian Army.

Getty Images

Getty Images

More surprisingly, Bassam Jamil, the former goalie, who went on to marry Yasser's sister, is a successful trader. He sells produce from local farmers - wheat, oats, beans, potatoes - across every front line.

"We even sell to the regime," he tells me down a bad phone line from Marea. "We don't mind selling onions to the regime! We do business with everyone - the Kurds, the regime, IS… But it's people, not regimes, I'm supplying!"

As we're speaking, he suddenly tells me the doors are shaking. Another bombing raid has started - this time from Russian jets. Russia's involvement in the war in support of President Assad has made life in Marea even more dangerous. But Bassam says he never bothers to hide.

"We're not going anywhere - there's nothing we can do," he says. "We've got a bowl of sunflower seeds here to eat and we're just working our way through them, like nothing's happening."

Equally pragmatic is Muhammad al-Najjar, the player with a touch of the Sylvester Stallone about him, the one they used to call Perfume Man. Always ambitious, he became mayor of Marea before the revolution - and to my amazement, he says he's still the mayor, even though the town has been in rebel hands for several years.

Muhammad al-Najjar

Muhammad al-Najjar

When I eventually get through to him - the line keeps breaking off - he says he's just brought salaries for town hall staff in Marea across the front line, from government offices in the regime-held part of Aleppo.

The rebels, who control the town hall building, don't acknowledge his status but he still manages to travel back and forth regularly - he now has two wives, one in each place.

Of course, the journey's not easy. Before the war it took perhaps half an hour. Now it can be eight to 10 hours, with various checkpoints to negotiate. And Muhammad al-Najjar lives with an additional, terrible, burden of anxiety. His son Haytham was kidnapped more than three years ago and has still not been released.

Muhammad al-Najjar

Muhammad al-Najjar

But Muhammad is determined to make the best of things. "I love everyone here in Marea and they love me, I swear," he says. "When I come over from Aleppo, everyone comes and welcomes me. People even congratulated me on my second marriage and brought me flowers."

His story is a reminder of how messy civil wars are. Not everyone belongs clearly to one side or the other, like they do in football matches.

But Yasser, who created the team, thinks there are some lines that can't be crossed. He always hated the government, even as a boy, and he says he'll never speak again to another player, Abdulrazzak, who now works for Assad's political intelligence service.

"I could say hello to someone else from the government side, but not someone from my own town, a cousin of mine, who knows exactly what happened - that in the beginning there were peaceful demonstrations, but they started killing us. That I cannot forgive him for."

With such divisions, it seems unlikely that the lads of the football team, now all middle-aged men, will ever all join up again to play another game.

When I started my search, I was afraid some might have been killed in the war. Luckily, they're all still alive - and most still in Syria, some in rebel-held and some in regime-held territory. But three decades on from the victories of Marea FC, their lives have been dominated by smashed hopes and by endless fear, both under Assad, and now through the war.

Today, Yasser al-Haji lives in Turkey and helps foreign journalists who want to cover Syria. Once sports-mad, he hasn't played football since he finally left Marea two years ago.

Muhammad al-Farouh

Muhammad al-Farouh

Meanwhile Muhammad al-Farouh, the star runner who spent time as a major in the Syrian air force, still plays football every Friday in his refugee camp. He runs the camp nursery school, with 800 kids. But he can't always handle the questions they ask.

"One child asked me why Bashar is the president of Syria when he bombs Syria, and other presidents don't bomb their countries," Muhammad says.

"And another kid who lost his father asked me: 'If I go back home, will my dad be waiting for me? Will he buy me the presents he promised?' Questions like that just make me cry, I don't know how to answer them."

No comments:

Post a Comment