A visitors' book from a tea room in Peterborough has helped reveal the extraordinary story of probably the first soldier of World War One to be accidentally killed by one of his own men.

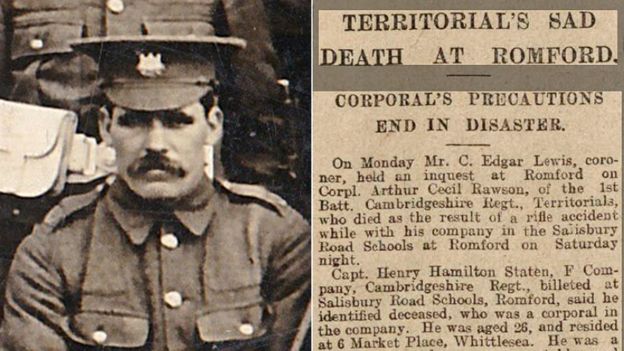

Cpl Arthur Cecil Rawson looks every bit the big, solid, square-jawed soldier in the F Company photo of the 1st Cambridgeshire Regiment, taken in 1909, the summer he joined the newly formed Territorial Army unit.

They were on their annual camp in Felixstowe, and the men of F Company were all from the market town of Whittlesey, so the lads knew each other well. Arthur, the son of a local grocer, apparently took to the role with gusto. His father had also been a volunteer in the Cambridgeshire battalion.

Apart from the annual camp, they did 40 drill nights a year, and each man had regular practice at marksmanship with his Lee Enfield rifle, known as the Long Lee.

By the summer of 1914, with tensions in Europe rising, and German troops on the march, the company was ready for action. Twenty-five-year-old Rawson had been promoted to corporal, and he was keen to make an impression on some of the younger lads, among them his 18-year-old friend Pte Alfred Davis.

The UK declared war on Germany on the night of 4 August 1914, and F Company were immediately mobilised and sent to Romford in Essex, where they were billeted in a local school.

Excited and full of anticipation, the men were issued with ammunition, and Cpl Rawson was tasked with organising guard duty. On the night of 8 August, a Saturday evening at about 23:00, after hours of patrolling, the six men were settling down for a rest.

Cpl Rawson was well aware of the risk from loaded weapons. He personally supervised the patrol group unloading the magazines from their rifles. When it came to Pte Davis's turn, he wasn't taking any chances. According to witnesses, Rawson told him: "Hand me your rifle and I'll unload it for you."

The men settled down in the corridor of the school, and Pte Davis was just drifting off to sleep, his rifle lying at his side, when there was suddenly the loud crack of gunfire. In the confusion Davis rushed outside, thinking they were under attack.

But inside, in the darkness, the men heard Arthur Rawson calling out: "Turn out the guard. I'm shot."

When the gas lights were lit, they found Cpl Rawson with a terrible wound to the thigh, and losing blood rapidly. He was rushed to the local cottage hospital where his leg was removed. But an hour after the emergency operation Cpl Rawson died.

It was the early hours of 9 August, just five days after war was declared, and before any British soldiers had even left the country.

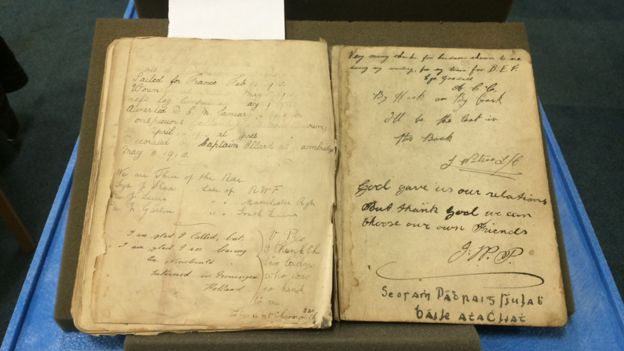

"I write here not for beauty/ I write here not for fame./ I write to be remembered/ So I'll just sign my name." (Pte J Ellis RGA, 5 July 1916)

"Two Kilties on their way from home to camp/ Crept here one morning cold & damp/ Then rested, washed, & hunger free,/ We took our leave, quite happy we." (Cpl L Thompstone, 2/4 Seaforth Hrs, 13 July 1916)

"Off with a Draft at last./ After eighteen months hard work,/ And should another War draw nigh/ I'll never join the 2nd Line." (Sgt JEH, 13 July 1916)

Alf Davis signed the book in March 1917, giving a brief synopsis of his later army career. He was sent to Belgium in February 1915 and became a stretcher bearer. In May 1915, at the battle of Fosse Wood, near Ypres, he was caught along with the rest of his unit in heavy machine-gun and artillery fire.

There were many casualties and Davis was awarded the DCM (Distinguished Conduct Medal) for bravery. The citation read: "For conspicuous gallantry as a stretcher bearer. He was seriously wounded in the attempt to bring in a wounded man under heavy fire."

Davis's injuries were so severe that he lost a leg.

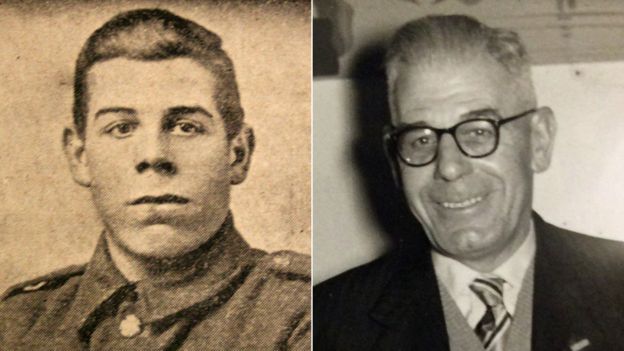

After the war he became a railway clerk and married, having three children. His youngest daughter, Margery Harrison, is now 92 years old and last week came to the Central Library in Peterborough to see her father's entry in the visitors' book.

The revelation about her father's accidental shooting of Arthur Rawson has come as a shock to Margery and her family. Like many ex-soldiers, she said he rarely talked about his experiences in the war with his family.

"I knew something had happened, but we never used to talk about that thing at home. He never used to say anything about what he'd done," she said.

I asked her what she thought about his role in the accident?

"I didn't know much about it. I knew something had gone wrong. It shook me when we read about it. It rather upset me. I was wondering whether those things really did happen."

The friendly fire incident was by no means the only example of troops dying as a result of such accidents.

Felix Jackson is a historian who has made a special study of the 1st Cambridgeshire Regiment.

He has uncovered five other fatal shootings and three serious injuries during the same month - August 1914 - at the very beginning of the war, all involving Territorial Army soldiers from other regiments.

Three of the killings involved soldiers being shot by mistake, and two other soldiers shot themselves by mistake while cleaning their rifles.

None of these incidents is cited when references are made to the earliest casualties of World War One.

Many accounts list Pte John Parr as the first British soldier to die in the Great War. He was killed on 21 August on the Belgian/French border, and there have been some claims that he, too, was the victim of friendly fire.

However, Cpl Rawson died 12 days earlier than Pte Parr.

Even earlier than that, though, on 6 August 1914, the cruiser HMS Amphion hit a German mine and sank, killing about 150 sailors.

Felix Jackson reckons Rawson has been forgotten from the history books because he died on British soil. "He didn't die in the face of the enemy," says Jackson, "It wasn't a morbidly glamorous death. "

He says more should be known about these early friendly fire incidents of WW1: "These were all men who'd volunteered. They were all in uniform at the time and they do deserve recognition and to be remembered."

Many politicians, including Lord Kitchener, the secretary of state for war, were scathing about the fighting skills of the Territorial Army. Kitchener called them "the town clerk's army" and considered them, unfairly, as amateurs and "play soldiers".

David Lloyd George, prime minister from 1916, wrote that on the evening after war was declared, Kitchener was "full of jest and merriment" at the expense of the Territorial Army, and called them a joke.

Lord Kitchener, who became famous with his wartime poster, wanted to raise an army from scratch saying he preferred men who knew nothing than those with a smattering of the wrong thing.

Matt Brosnan, a historian from the Imperial War Museum, says as the war continued the numbers of friendly fire casualties increased dramatically.

One of the major causes was what was known as the "creeping barrage", a curtain of artillery shells which were fired slightly ahead of advancing troops, but which often missed their targets, hitting their own soldiers.

"The shells were slightly indiscriminate," he says. "Sometimes a dud shell for example fell short. Those kind of friendly fire incidents particularly happened on the Western Front where artillery was such a dominant weapon."

No comments:

Post a Comment