Pope Francis has made moves towards reform - but can he overcome a bedrock of opposition, asks Sarah Dunant.

Looking back on it I think I was about 10 or 11 when the sacrament of confession worked best for me. I have vivid memories of a sense of burden as I entered the confessional box. Had I

remembered all the things I'd done wrong? Was I truly sorry for them? Equally powerful was the relief that came upon me afterwards. Penance was never hard - a few Hail Marys next to a colourful statue of the Virgin crushing a snake underfoot - and walking home everything seemed suddenly brighter. I was forgiven, absolved. The world, and I inside it, felt new again.

I have been revisiting that feeling as I watch the titanic struggle now going on within the Catholic Church, a Church which I left in my late teens, committed by then to a different kind of new world.

Pope Francis's calls for mercy, forgiveness and a priesthood truly at the service of the laity is at the heart of a reform that, if successful, could transform the nature of Catholicism as we know it. It's as if the Church - the institution itself - is being asked to enter the confessional, acknowledging its sins in readiness for a new start.

Both systems, one might argue, had become unfit for purpose. In the case of the Catholic Church, the long pontificate of John Paul II with his charisma and popularity obscured this reality, shielding entrenched financial corruption and a hierarchy increasingly out of step with the modern world, though not even he could ignore the gathering tsunami of sexual abuse and cover-up. As the scale of the problem emerged, Europe in particular suffered. Recruitment to the priesthood and closed orders dropped radically. Over the last 15 years in Ireland, Spain and especially in Italy (where I work part of the time), churches seemed to grow bigger as congregations grew smaller. And older - the dwindling of numbers a particular problem when it comes to women who, ironically given their lack of power, have traditionally kept the flame alive in the family. Worldwide, the numbers of Catholics may still look healthy, but in Europe, the centre of its history and government, there is clearly a crisis.Though communism and Catholicism have little in common one can't help but find it reminiscent of the perestroika moment when Gorbachev opened up a closed corrupt system for reform.

If that old adage learning from history has any meaning, one can only look in awe to another historical parallel, this one within the Church itself 500 years ago.

The sins around 1515 were largely the same - humanity remains fond of two in particular - fornication and avarice. Popes had children, cardinals had mistresses, priests had housekeepers, monks occasionally had each other and childhood, which effectively ended at 12 or 13, was fair game to those in power whatever their proclivity.

Financial corruption was systemic. Palaces, parties, patronage - the use of Church money to feather the nests of those working for it makes the recent scandal of the German bishop with his 15,000-euro bath tub look like a visit to Homebase. Looking back on it now you might argue that part of that outrageous wealth went into great art; stand in the middle of the Sistine Chapel and weigh up charity against beauty. The truly egregious fault was less what they did with it than how they got it - selling indulgences and auctioning offices in an ever-expanding bureaucracy.

Then, as now, there were voices pushing for reform. The Church has always had a strong pull towards the Franciscan vision - poverty and humility against ceremony and authority. Years before the election of our modern Pope Francis, Carlo Maria Martini, cardinal and archbishop of Milan, was openly critical of the Church's stance on sexuality and contraception. In a final interview before his death in 2012 he called for a radical transformation, beginning with the pope and his bishops. Pope Benedict did not attend his funeral. Meanwhile in America, nuns were devoting more of their time to pastoral and social work outside the cloisters, only to find themselves under papal investigation to root out "certain radical feminist themes incompatible with the Catholic faith".

Francis's election in March 2013 took place 500 years almost to the day after that of Leo X. Son of Lorenzo de Medici and a career churchman (he was cardinal at 18), his comment on winning - accurate in spirit if not his actual words - was "since God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it". So the pope "fiddled" as Rome started to burn.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo Library

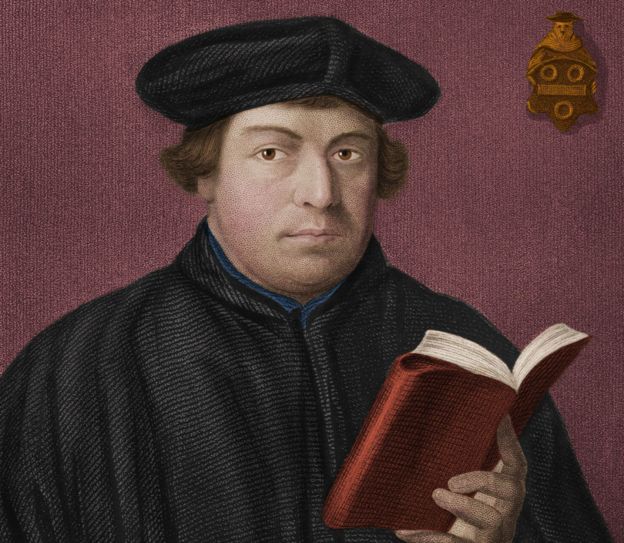

The spark of course came from Germany four years later when the Augustinian Martin Luther took reform into his own hands. Among the many broadsides he launched, perhaps the most significant in terms of the crisis today was against celibacy (he went on to marry a nun). The Catholic Church's response through the counter-reformation was retrenchment. The doctrine of celibacy - singleness and sexual purity - would continue.

Fast forward to October 2015, when the Polish priest and theologian Krzysztof Charamsa, gay and proud with his partner, left the curia by means of a press conference on the eve of the family synod, accusing the Church of hypocrisy and homophobia. Who could doubt his honesty? Or the viper's nest of infighting it revealed inside the Vatican?

EPA

EPA

Behind the critique of the gay lobby is a much deeper one. Men may truly believe in God but for most of them chastity is too big an ask and if enforced, leads, at worst, to abuse and at best to a clergy and hierarchy ignorant of, and often unsympathetic to, the problems of being human. From there it's but a skip and a jump to the role of women and their exclusion from the heart of the Church.

History again is the key. By denying the sacramental nature of the priesthood, the reformation gave women, potentially at least, a bigger voice. Even at its most conservative - think Victorian Anglicanism - the vicar's wife was still in his bed, mothering his children and shouldering parish duties, often specialising in compassion and charity. Thus when the second wave of feminism hit, hand in hand with gay politics, women had less distance to climb into the pulpit, though their ascent caused some Anglican minsters to convert to Catholicism, swelling the ranks of the conservatives.

iStock

iStock

Anyone under the age of 35 will have lived most of their adult life in a country with women priests. For the rest of us, any shock has long since disappeared. As too will the hoo-haa over women bishops. Whatever the difficulties, within Anglicanism the rise of women seems unstoppable. Within Catholicism it remains inconceivable.

So let's, just for the hell of it, allow our imaginations to run riot. What might a reformed Catholic Church look like? Start with small steps - allowing communion to divorced or co-habiting couples, the Church not judging gay men in loving relationships (both positions Francis himself has espoused). From there we move to a greater acceptance of homosexuality in general, even to same-sex union and families. How long before we hit celibacy and women priests? At which point there are women in the faith who would want to widen the debate, to suggest that it is the whole notion of an elevated priesthood and hierarchy that needs addressing, encouraging more democracy and community as a way to get better shepherds for the flock.

Enter a religion defined by God's mercy and inclusion, with a strong voice on issues like market excess and climate change and where men and women shared spiritual power. In a world under attack from testosterone-driven fundamentalism - I could have written exactly those same words before the events in Paris, but somehow they mean even more now - that is a religion even I might be tempted to join. Though how many Catholics I would find sitting next to me in the pews is a big question.

Inconceivable, clearly. In the real world, Francis' milder reforms have already hit a bedrock of opposition. Consider how little the recent family synod really moved its position on anything. Dragging one's heels is a powerful strategy used against a man who will be 80 next year.

Getty Images

Getty Images

But this Pope's legacy will be two-fold - what he can achieve in his lifetime and what will happen after him. I throw in a final card from history. Conclaves may be open to the word of God, but they are also about mathematics. And humble though he may be, Francis is not innumerate. In his appointment of new cardinals - nearly 40 over two years - he has turned his back on established career paths, favouring instead clerics from the developing world. Give him another four or five years and the make-up of the next conclave could be dramatically different. In which case his successor won't need the six mules loaded with silver with which Rodrigo Borgia bought off his chief rival in 1494.

If I was still a Catholic, that would be something to pray for.

No comments:

Post a Comment